americký Čech Joe Lapchick. Dnes si predstavíme práve Lapchicka, legendárnu postavu basketbalovej histórie.

Joseph Bohomiel Lapchick

Narodenie: 12. apríla 1900, Yonkers, štát New York, USA

Úmrtie: 10. augusta 1970, Monticello, štát New York, USA

Výška: 196 cm

Váha počas aktívnej kariéry: 84 kg

Pozícia: center

.Basketbalová kariéra.

1912/1913 Holy Trinity Midgets

1913-1915 Yonkers Hollys

1915-1918 Hollys, Ossining Bantams

1918/1919 Hollys, Bantams, New York Whirlwinds

1919/1920 Hollys, Whirlwinds, Holyoke Reds

1920/1921 Hollys, Whirlwinds, Reds, Schenectady Dorpians, New York Wanderers

1921/1922 Reds, Dorpians, Troy Trojans, Brooklyn Visitations, Mt. Vernon Armory Big Five

1922/1923 Reds, Trojans, Visitations

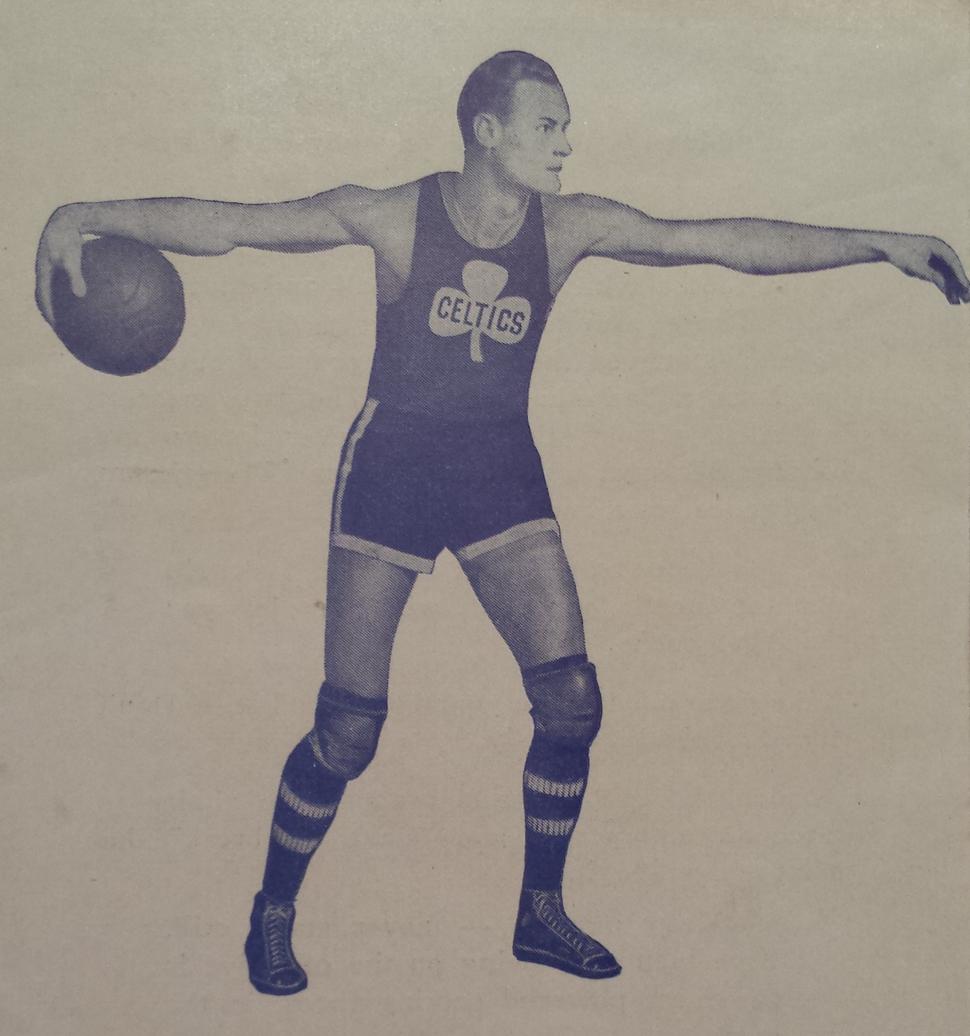

1923-1928 (New York) Original Celtics (v sezóne 1927/28 nastúpil jeho brat Willie za klub z Brooklynu)

1928-1930 Cleveland Rosenblums

1930/1931 Toledo Red Men Tobaccos

1931/1932 Original Celtics

1932/1933 Original Celtics, Yonkers Indians

1933/1934 Original Celtics, Plymouth Shawnees

1934-1936 Original Celtics

.Trénerská kariéra.

1930 Cleveland Rosenblums

1936-1947 St. John's University

1947-1956 New York Knicks

1956-1965 St. John's University

.Ocenenia a úspechy.

Uvedený do Basketbalovej siene slávy v roku 1959 (ako člen Original Celtics) a 1966 (ako hráč)

4x šampión ligy ABL (1927, 1928, 1929, 1930), 1x šampión Interstate Basketball League (1922)

3x finalista NBA (1951, 1952, 1953)

3x kouč NBA All-Star výberu (1951, 1953, 1954)

4x šampión najprestížnejšieho vysokoškolského turnaja NIT (1943, 1944, 1959, 1965)

***

Odporúčam pozrieť si tento krátky dokument o Lapchickovi:

***

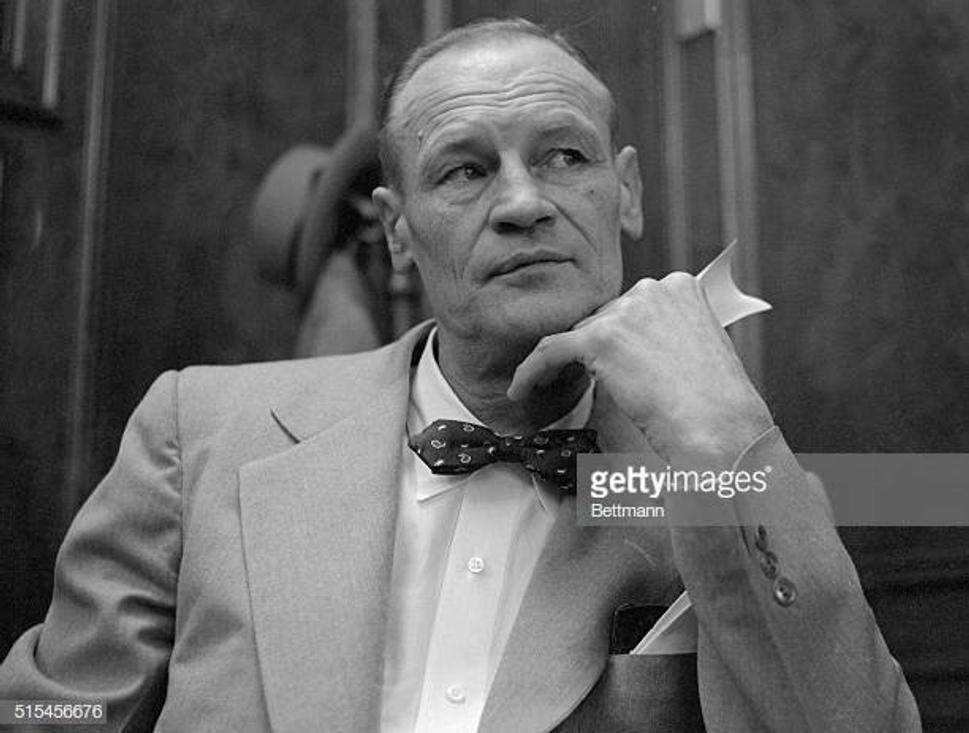

Pred dvanástimi rokmi vyšla o Lapchickovi skvelá biografia s názvom Lapchick: Život legendárneho hráča a kouča v slávnych dňoch basketbalu. Autora Gusa Alfieriho, bývalého Lapchickovho zverenca na univerzite St. John's, som požiadal, aby napísal o Lapchickovi krátky blog, a Alfieri súhlasil aj so zverejnením prvej kapitoly svojej knihy. Tá je pre slovenského a českého čitateľa asi najpútavejšia, pojednáva totiž o prvých dvadsiatich rokoch Joeovho života, jeho českých rodičoch, meste Yonkers, kde Lapchickovci bývali, Slovákoch v tomto meste, a začiatkoch Lapchickovej basketbalovej kariéry. (Pre nás najzaujímavejšie časti som označil tučným písmom. Pokiaľ neviete anglicky, odporúčam prekladač DeepL, je naozaj výborný.) Počas Lapchickových päťdesiatich rokov v basketbale sa z neho stala jedna z najváženejších osobností v tomto športe a aj na trénerskom dôchodku sa tešil veľkej obľube športových novinárov. Po odchode z St. John's sa dal na písanie a výsledkom bola kniha 50 rokov basketbalu, v ktorej píše o svojej trénerskej filozofii a príbehoch zo svojich hráčskych dní. Okrem toho pracoval ako športový koordinátor v country klube Kutsher's. Zomrel v 1970 na srdcový infarkt; zanechal po sebe tri deti, dcéru Barbaru a synov Joea mladšieho a Richarda, rešpektovaného aktivistu za ľudské práva, akademika a autora mnohých kníh.

***

Gus Alfieri: Joe Lapchick a znovuobjavenie starých hodnôt

To, čo Amerika a svet potrebuje, a potrebuje súrne, je znovuobjavenie starých hodnôt. Takých, aké mal môj starý vysokoškolský tréner Joe Lapchick. Keď si spomeniem na to, ako sa tento muž správal, v dnešnom svete by nad tým nejeden človek pozdvihol obočie. Keby ľudia poznali jeho príbeh, možno, snáď by sa niečo z jeho prvotriedneho charakteru nalepilo aj na nich.

Joe Lapchick preukazoval charakter tým, ako zaobchádzal s ľuďmi. Nerobil žiadne úsudky na základe toho, že boli chudobní alebo nemali vzdelanie, neohŕňal nad niektorými nos alebo nadbiehal tým, ktorí mu mohli urobiť láskavosť. S každým zaobchádzal rovnako. Myslím, že to, že bol príjemný k ľuďom, aj keď mal stresujúce povolanie kouča, robí jeho sociálne správanie ešte viac výnimočnejším.

Keď sa Sweetwater Clifton stal prvým černochom, ktorý v roku 1950 podpísal NBA kontrakt s New York Knickerbockers, Lapchick s tým vrele súhlasil. Lapchick sa postaral o to, aby integrácia pre hráčov Knicks a Cliftona fungovala, tým, že s Cliftonom zaobchádzal takisto, ako keby koučoval akéhokoľvek iného hráča. Zatiaľ čo pomáhal Cliftonovi s integráciou do mužstva, Lapchick a jeho rodina sa museli brániť pred osobnými urážkami, trpieť neskoro večerné telefonáty a dokonca aj incident s jemu podobnou figurínou visiacou zo stromu, ktorý sa stal pred jeho domom v Yonkers. Avšak Joe Lapchick preukázal charakter už aj predtým, keď v povojnových rokoch koučoval na univerzite St. John’s.

Bob Cousy bol nešťastným vysokoškolským hráčom, ktorý bol považovaný za najlepšieho playmakera na pozícii rozohrávača v krajine. Na vysokej škole Holy Cross začínal byť viac a viac sklamanejší a rozhodol sa teda napísať Lapchickovi, či by nemohol prestúpiť na St. John’s. Lapchick vedel, že má povolenie získať tohto zmäteného športovca pre svoj tím a viesť tak jedného z najlepších mladých basketbalistov, ale rozhodol sa inak.

„Zostaň na škole. Tvoj kouč je skvelý chlap a okrem toho, prestup na inú školu často prináša viac problémov, ako teraz zažívaš.“ Týmito slovami presvedčil budúcu hviezdu NBA, aby zostala na škole, a urobil to, čo považoval za férové a správne.

„Som zvedavý, že koľko iných koučov by ma presvedčilo, aby som zostal na Holy Cross a neprestupoval na St. John’s,“ povedal neskôr Cousy, ktorý toto leto oslavoval 90 rokov. „Do dnešného dňa som za tú radu Joeovi Lapchickovi vďačný.“

Nemôžeme čakať na to, že médiá začnú písať o charakterných činoch v športe. To proste noviny nepredáva. Ale naši školskí a občianski lídri, spolu s rodičmi a športovými trénermi, musia dať charakteru znovu najvyššiu prioritu a nájsť spôsoby, ako docieliť, aby naša mládež pokladala pozitívne hodnoty za dôležité.

A možnože keby sa viac pozornosti venovalo charakteru osobností ako Joe Lapchick, návrat k spôsobom minulosti by sa mohol stať realitou, namiesto toho, aby ostal len nemožným snom.

* * * * *

The St. John's Redmen just won the 1959 National Invitational Tournament. The Redmen were winners. He did it. Joe Lapchick’s mental toughness and homespun philosophy shaped by Rudyard Kipling's poetry taught him to keep his head when “others were losing theirs.” He was no longer the washed up Knicks’ coach or haunted by past nightmares from his return to St. John’s, where he feared his team was “in the tank.” He was on top again, and it felt good. It was quite simply “the most gratifying season” he’d ever had.

The team was thrilled, but no more than its coach. It was all sinking in. It seemed only yesterday in the same surroundings Lapchick packed his bags under duress and left the New York Knickerbockers. He felt uncomfortable with their maestro Ned Irish, whose button-down polish rubbed him wrong. But today the victory masked that feeling.

"The Old Coachie," the way he ended letters late in life, proved he could still mold champions by convincing a bunch of kids to believe in themselves and follow the yellow brick road to the winner's circle. As cameras clicked and player merrymaking ballooned, Lapchick's mind wandered, not to the postgame party at Leone’s, but to his start in basketball, back to the Yonkers tenement where it began with a ball made from a stuffed, blue serge hat.

* * *

“Pass the ball, Joe,” his teammate, Michael Turczyk from Nepperhan Avenue, called out. The blond Joe Lapchick was exceptionally tall for a ten-year-old, and as he held the homemade ball over his head out of reach of the smaller competitors, he surveyed his options. Out of the corner of his eye he spotted Dave Kurbask open, flipped him the ball, and Kurbask shot it over the ledge of the entrance to Joe’s tenement. “Two points,” his teammates yelled as Turczyk retrieved the ball.

Like many kids in 1910 from the Hollow of Yonkers, New York, a sprouting Joe Lapchick had shifted his attention to basketball, the new exciting street game. When equipment was unavailable, he and his friends imaginatively improvised games in front of his Mulberry Street tenement. They used a cap filled with paper stuffed into an old discarded soccer ball to give it a round shape. Throwing it onto the short entrance roof scored points.

The same beat-up soccer ball was used for another version of the new game on the main streets. The makeshift game was played by “circulating around ice wagons,” Lapchick recalled and passing the ball to teammates “under the bellies of teams of horses.”A score resulted “when we maneuvered and could toss the ball between the legs of the walking horses.” The Yonkers youngsters added a new skill, the dexterity of throwing it past a moving object.

Joe’s folks knew little of sports. Mrs. Lapchick worried about her son’s schoolwork and his help around the house. Mr. Lapchick worked long hours as a motorman on a trolley line, more concerned with putting food on the table.

Joe often talked to his father about the old country. “What was it like?” Joe asked one night after dinner. Mr. Lapchick looked up from the Yonkers Herald to answer his interrogator. “What do you want to know, Joe?” his father asked. “How did you get to America, what did you do as a boy in Bohemia?” His father put down the papers, and cleared his throat. “It all started in the town of Zlín.”

* * *

Josef Lapčík looked no different from any other fourteen-year-old Bohemian Czech from the Austro-Hungarian Empire who came to America. Huge waves of immigrants poured into America from Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century and every tale of departure was unique.

In need of work, Josef was offered a gardener’s job on a large estate of a wealthy German baron from the nearby town of Zlín for the equivalent of ten cents a day. He reported for work dressed in a long, crude, cotton wheat-colored tunic blouse and a straw hat with a blue string ready to wrestle weeds in the beet fields from early morning until dusk. As an escape from the hot afternoon sun, the young Czech found an occasional rest appealing.

One day the suspicious baron found Josef napping under a tree in the rose garden where he had been sent to weed. Discovering the youngster asleep, the landowner trashed him for “stealing his money” and dismissed him.

When word circulated in the Lapčík family that an uncle was returning to America, Josef jumped at the opportunity. He sailed in 1890 and arrived three weeks later at the Battery in Castle Garden, New York, among the first Czechs in America. “Joseph Lapchick,” the immigration worker called out, as he scribbled his new name on a pass into the new world. In an instant, as he pushed through the doors into downtown New York, he left his old world, and name behind, and entered a bright, new exciting adventure. After a series of jobs that took him from upstate New York to the Pennsylvania coalmines, Joseph settled in Yonkers, where he found steady work in a hat factory.

One cold winter day, after he was settled in Margaret McCrudden’s boarding house, he decided to explore Yonkers. Walking to Broadway, its main street, he crossed dirt roads that reminded him of the cow paths back home and noticed livestock scurrying to avoid horse-drawn carriages hauling supplies. The main streets were filled with an unfamiliar industrial energy and bustle.

Provision stores like Finkelstein’s Butter and Eggs on Riverdale Avenue sold neatly wrapped packages of goods never seen in his Slavic country. Other store windows offered sacks of Hecker’s Flour along with more familiar rolls of kielbasa and pickled herring for a few cents a pound. Strong fresh aromas drifted from bakeries selling crisp loaves of rye and black bread at five cents each, with no signs of shortage. Down the street was a cigar store and Culver Dry Goods that seemed to him to house more clothing than the Emperor’s soldiers could use in a lifetime. Burstell’s Fishing and Tackle Shop alerted the youngster to Yonkers’ hobbies, but was mystified that the shopkeeper was “a locksmith.” Next was Gideon Peck’s store, which sold and carefully blocked felt hats. The streets were an education to him.

As he continued walking in the bitter cold, he came upon the White House Hotel, a handsome building, fancy and bright, with a large iron trough in the middle of the square for horses to drink. He came to realize Americans did not always sleep in their own beds. His adventurous walk took him past establishments that sold newspapers. Yonkers in the 1890s had four dailies, and people sat in restaurants or grouped on the streets with friends to openly discuss the news. That impressed the young Czech who remembered free speech discouraged under the emperor. As he walked past Pier Street, he found an icehouse, learned Americans paid a few pennies for large blocks of ice to preserve food in iceboxes in their homes, and didn’t have to bury it in the ground as his family did.

An unlimited number of saloons served beer that made some men argue and fight as they did in Europe. There were saloons on almost every corner with short swinging doors, brass spittoons and rails, and highly polished mahogany bars counters with mirrored walls. Their magnificence was breathtaking to Joseph. Americans, he thought, have so much money they can build fancy saloons.

One intriguing storefront caught his attention: “Forestiere, Undertaker.” What was an undertaker, he wondered? He later learned they buried the dead and handled all family arrangements. There was much to understand. Joseph tried to absorb all of it, to digest it slowly as his uncle suggested.

His boarding house was located in the Hollow by Holy Trinity Church, which brought him in contact with Eastern Europeans with whom he could converse in many Slovakian dialects. Within a few months he was speaking better English and felt more comfortable in the new world everyone raved about.

At a church dance several years later he was attracted to a young blond-haired girl who would later become his wife. Although Františka Kašíková came from similar Eastern European roots it took a three thousand mile journey for them to meet. Born in Russia (Pozn.: bola etnická Češka z Haliče.) in 1883, Františka arrived in America four years later and settled with her Czech family in Haverstraw, New York. A lack of steady work forced them to move to Yonkers.

Six months after she met Joseph, they were married. Frances was sixteen and Joseph twenty-three when they took a tenement flat near her family. Yonkers was bursting with life at the dawn of the twentieth century. The Terrace City of hills and valleys had a growing population of more than 47,000. With its beautiful stone formations, it seemed a paradise, one neither they nor their children would abandon.

* * *

The Hudson River bordered Yonkers on the west, which encouraged end of the century aristocratic roots to form. The Flagg and Untermeyer Estates blended with the obvious affluence of "Millionaire Straphanger" John E. Andrus, who would later regularly subway to Wall Street. Impressive Victorian estates lined Warburton Avenue and afforded the wealthy a breathtaking view of the Hudson River.

By the early part of the twentieth century, America had grown from an agricultural society to the world's leading manufacturing nation, with Yonkers reflecting its transition. Its hilly landscape projected majestic energy that is still present today and was an idyllic setting for immigrant Americans adjusting to a new world in a new century. The thriving industrial community’s catalyst to economic growth was its access to the Hudson. Besides hat manufacturing, the world-famous Smith Carpet Factory, which employed more than 7,000 and the Otis Elevator Company, provided work for the overflow of immigrants.

A working class world emerged east of the picturesque and affluent Hudson River estates. The Hollow consisted of 174 acres encircled by Nepperhan, Yonkers and Ashburton Avenues. At the turn-of-the-century, the beveled-shaped Slovakian community attracted Poles, Czechs and Hungarians, who found six-day a week employment in the mills. It was rumored arrivals were escorted to the factories from Ellis Island to ensure a steady flow of much-needed cheap labor.

The Hollow was filled with cold-water railroad flats, which provided the bare necessities of drinking water and kerosene-heated stoves that threw off enough heat in the winter to dry clothing. Slovakians were a clean, neat people who banded together around their religion to help each other in time of need. Life was hard, as Joe Lapchick later pointed out about his youth, but there was a realization that the new Americans were carving out a better life for themselves and their children.

* * *

On April 12, 1900, on Holy Thursday, a bright-looking blue-eyed baby boy, Joseph Bohomiel, the first of seven children, was born at 324 Nepperhan Avenue near the Hollow of Yonkers to Joseph and Frances Lapchick. His mother liked the Czech name Bohomiel because it meant “God’s love,” and showed religious respect. Their son would share an April 12th birthday with Thomas Jefferson, one of America’s great presidents and with a new millennium that turned a futuristic corner when it was announced that 75,000 telephones were in service in New York City.

A unique bond existed between the Lapchicks and Yonkers. The family never left its boundaries once Frances and Joseph planted their roots. Their seven children - Joseph, Edward, William, Emily, Anna, Frances and Florence - and their parents lived in Yonkers and were buried in its Oakland Cemetery on Ashburton Avenue.

On a warm summer Sunday Joe and Frances Lapchick wrapped their firstborn in a blue cotton blanket and made their way across Walnut Street to the Catholic Slovak church. Holy Trinity with its tall steeple, slanted roof, and Romanesque arches, where the young couple had married a year earlier, baptized their son.

Joe, Sr. was a big, strong-looking man with huge, powerful arms and a pair of hands toughened from his agrarian youth in Bohemia. Young Joe would later acquire physical characteristics from both parents, resembling more his mother’s narrow frame, blond hair and high cheekbones while inheriting athletic advantages from his father's large hands and long arms.

Religion was a force that bound Czech immigrants, shaping their appreciation of life's blessings while helping them endure economic hardships. The nationalistic church was the pillar of life for most Slovakian Catholics in Yonkers, as well as the Lapchicks.

Sundays to most Slovakians in the Hollow were reserved for Church. They felt at home hearing mass in their native tongue and socializing with people from the old country. When the Lapchicks moved from the Hollow, they remained part of the church the rest of their lives. While the Slovakian community lacked comforts, its residents never felt poor. Although Mr. Lapchick at first made eight dollars a week as a hat maker, the family was happy in its struggle. The Hollow's shortcomings were balanced by the community’s neighborly concern for one another. If one family had a problem, all helped; it was where extended families lived and pooled their money, while keeping their tenement flats neat and clean.

The Czech couple’s faith strengthened young Joe, encouraging him as he grew up to practice his religion and be content with what God provided. Catholicism remained a strong part of his life, and his cultural pride in his roots was the catalyst for Joe Lapchick’s accomplishments. Growing up young Joe learned to respect God. In a practical way, he later looked at religion as an insurance policy, one that encouraged regular payments. "After a Saturday night Garden game,” Knicks trainer Don Friedrichs recalled, "Joe and I would dash over to St. Francis of Assisi's Church and catch the Printer's Midnight Mass before we headed to Boston." When he flew with his St. John’s team in the late 1950s, he carried a rosary inside his overcoat pocket.

* * *

At the start of the new millennium Yonkers had a rich athletic tradition and Joe was drawn to a variety of its sports. At the age of nine Joe was first attracted to golf. He was tall enough for his age to fool Jack Mackie, the golf pro at Dunwoodie Country Club into believing he was twelve. As soon as the Sunday seven a.m. mass at Holy Trinity ended and before the priest genuflected to leave the altar, Joe flew down the side aisle and out the back door running all the way to beat the other caddies to line up. “You, the blond kid in the rear,” Mackie yelled out, pointing to him, and he was off on another eighteen holes.

Caddying allowed him time to study golf and learn from some of the club’s best golfers. His biggest thrill came while caddying for pro great Francis Ouilet shortly after his US Open upset victory in 1913 over England’s best.

The young caddy got to meet other Dunwoodie golfers like baseball legends, Fred Merkle and Christy Mathewson of the New York Giants, who were good golfers and good tippers. The big Czech kid liked them and tried switching in line to carry their bags. However, he wasn’t crazy about entertainers. Actor Douglas Fairbanks Sr., who lived in Yonkers along with his actress wife Mary Pickford, made him uncomfortable with his British accent and swashbuckling gyrations. Al Jolson was more Joe’s speed, since the famous popular singer came from poverty and spoke the caddy’s language. While learning golf, Joe was also being taught how to conduct himself among men of the world, knowledge he stored for future use.

With the luxury of a taped-up ball and a bat, the neighborhood baseball buffs played pickup games at the local park. However, Joe liked playing on Mulberry Street’s cobblestones. Some days they organized One O’ Cat stick ball games, using a broken broom handle and a soft rubber ball. Joe liked batting and quietly enjoyed the praise from his teammates when he hit “three sewer covers” over an outfielder’s head. Street games supplied hazardous excitement for the boys trying to sidestep moving, thousand-pound horse-drawn delivery wagons. Occasionally Joe was spooked by a loud horn from new automobiles that were beginning to compete for street space.

Besides eventually teaching himself to be a pro level golfer, he later became a talented semi-pro sidearm fastball pitcher, dreaming of being a major leaguer. He eventually had opportunities in both sports. Later, the Brooklyn Dodgers wanted to sign him, but by then his passion was basketball.

* * *

As the oldest, Joe liked earning money to help his family. Although the cold-water flat on Mulberry Street was adequate for the expanding family, there was little money for extras. His mother’s Slavic diet of stuffed cabbage and mushrooms spiced with occasions of kielbasa and walnuts kept body and soul together.

“Joe, run to the Company Store and pay our bill,” his mother would tell him. In the Hollow it was customary for family’s to keep a small “credit book” of groceries with the local store. Trust was important in the Slovakian Hollow and formed the backbone of its people. “We owe $5.93, and when you pay make sure Mr. Sarmast signs the book,” Mrs. Lapchick reminded her son. Joe ran to the neighborhood store, paid the bill and picked up additional groceries his mother needed. His golf tips helped feed the family because his father’s motorman salary didn’t travel far enough. On good days he made as much as $1.35, which paid for a side of pork the length of his arm and a week’s bread for the whole family.

The Lapchicks taught their children to waste little. Brother Bill Lapchick had vivid recollections of Joe picking coal wherever he could. "Joe would go down to the Hudson River with a kid's wagon and load it up with pieces of coal dropped on the New York Central tracks,” to help cook and heat the family’s flat. He learned to be frugal; something that was ingrained into him from his early days and later passed onto his children. But when not helping his parents, Joe liked to play sports.

Athletic clubs were popular in Yonkers, and encouraged competition among the many organizations battling for local bragging rights. The neighborhood was alive with sports for youngsters from road running to baseball. Joe’s interest in baseball led him to volunteer as water boy for the local Federal Sugar Factory team. He looked up to local heroes and didn’t mind chasing balls that went over the fence or got lost in the weeds. He liked warming up pitchers and dreamed of following in their footsteps. It was fun. Sometimes, however, Joe emulated older athletes too well. Watching teenage baseball players got Joe interested in smoking. After games, several got together for a cigarette. One removed a pack of Sweet Caporals from his game bag and passed it around. Although Joe had never seen the brand before, the picture of Honus Wagner, the great Pittsburgh Pirate shortstop, on the white cigarette package attracted him.

“Do you want one, Joe?” He had never smoked but remembered it seemed fascinating. He took one and jabbed it into his mouth and one of the players lit it for him. He took a deep drag as he saw the others do. When he coughed, they laughed, but he didn’t mind.

For a few pennies Mr. Kruppenbacher’s Stationer’s store made a big kid feel older. “Can I have three loose cigarettes for my father?” a tall nervous ten-year-old asked. The wise owner sized up the situation, one he experienced daily. “What brand does your father smoke?” the owner questioned. Joe looked for the ones the baseball players smoked but didn’t see them. He saw another brand behind the glass case counter that he vaguely recalled. “Derby,” Joe answered more confidently. The storeowner handed the cigarettes to the boy who reached into his pocket for three pennies.

Joe learned to smoke at a young age, a time when there was less attention paid to the hazards of smoking. He usually smoked before dinner when he had money, but made sure none of the cigarettes were left in his pants pockets for his mother to find. He had seen his father take deep breaths on a cigarette. It seemed fun and harmless. Joe didn’t think it would interfere with his passion for sports as rumored and especially for the new sport gaining attention.

* * *

In December of 1891 with the onset of winter, James Naismith and the other professors at the YMCA training school in Springfield, Massachusetts, had difficulty running indoor physical education classes. After two colleagues failed to tame a restless class of eighteen rugby-football players, Naismith had an idea he thought might work. The game was not to be a variation of football but was to have its own identity.

"In the fall," Naismith wrote, "We decided that there should be a game that could be played indoor during the winter seasons." By making the ball large enough to discourage running with it, Naismith felt the game would favor skill rather than rugby violence.

Ideally, basketball was designed as a game of finesse, centering on shooting a ball at an elevated stationary target with a scoring system involving a goal through which the ball could pass. To prevent interference with a scoring attempt, Naismith made the goal horizontal and placed it above the players' heads. A raised target discouraged them from gathering around it. Naismith believed this innovation was the new principle that was needed. As a former football player, he felt it best not to have players run with the ball but pass it, and the seeds of a passing game were born. Unlike soccer, a player’s hands could control the ball. A field goal was valued at two points, a free throw after an infraction of the rules, a single point. Naismith's game was shaping up.

When he asked the building superintendent for two average-sized boxes, all he came up with were a couple of peach baskets that narrowed at the bottom. “I found a hammer and nails,” Naismith said, “and tacked the baskets to the lower rail of the balcony, one on either end of the gym.” At the beginning the ball was caught in the basket, but later the bottom was opened for it to fall through. The height of the balcony accidentally fixed the basket at ten feet, making it forever sacred, surviving even the ravages of todays seven-footers. After much thought, Naismith launched the game with a set of simple rules and two discarded, cone-shaped peach baskets.

The first game was played in the school’s basement on a court 35x50 with eighteen students forming two nine-man teams. They played in long pants with long-sleeve jerseys, and most of them sported stylish walrus mustaches like their professor. The first ball used was a regulation-size volleyball. One goal was scored, with the game ending 2-0. After a brief trial, a student suggested it be called Naismithball. However, the good doctor rejected that notion, permanently baptizing it basketball.

The number of players varied from seven, to eight, even nine, but eventually settled on five per team. Playing time was at first three, twenty-minute periods, later reduced to two. When balcony spectators interfered with the ball's flight, a backboard was added. Through its immediate popularity and the stimulation of YMCAs and athletic clubs, basketball became the most popular indoor sport. Basketball had obvious appeal. Its simple but skillful point-scoring objective encouraged exciting play and helped it catch on. The game offered plenty of exercise while requiring little space or expensive equipment. There were no regional or climatic barriers. You played in hot or cold weather, urban or rural settings. It attracted Midwestern wheat farmers as well as Eastern street-smart city kids. Playing areas were easily assembled, both in and outdoors. A hoop could be nailed to a barn door as well as a tenement building. Athletes from all social classes played, and a solitary player could have fun shooting a ball for hours. It was a sport for Americans by Americans.

Since basketball had an Eastern start, New Yorkers in particular adopted it as their City Game. Ball handling, defense, and percentage shooting were its trademark, and it blossomed in urban playgrounds. Smart passing forced defensive errors and became the stamp of metropolitan New York's play, where many of the nation's best still develop.

Another approach to the game was launched in the Midwest where Indiana’s up-tempo play became popular. It featured an offensive game centered on running and high scoring more than defense. Since the 1910s, Indiana's high school tournament electrified Hoosier towns. Both styles, however, insisted their basketball was the best.

Work theories of the era like Frederick Taylor's Scientific Management made more time for entertainment. New industrial twentieth century America was learning to relax and enjoy its leisure time. While fascination with baseball dominated America, amusements in the 1890s, like Coney Island and the Chicago World Exposition, captured international attention. The growing urban population was being entertained as participants or spectators, and the nation was ripe for new approaches to sports.

The new sport was further helped by the expanded interest in athletic clubs throughout the Northeast. The elite joined country clubs to play golf and tennis, leaving sandlots and city streets as playgrounds for working class children.

From the post-Civil War period athletic clubs helped spark sports competition. The best one was the New York Athletic Club, the prototype for others that mushroomed in the Northeast. But, by the 1880s, interest in a variety of sports encouraged new athletic clubs to build gymnasiums, while high schools and colleges made sports a bigger part of student life. With interest in sports and leisure time on the rise, basketball developed.

In 1894 the Alexander Smith Carpet Mill of Yonkers built the Hollywood Inn as a “club for "workingmen," and as a benefit to their morale. While the Hollywood Inn was the brainchild of Yonkers businessmen, it was carpet factory owner and philanthropist William F. Cochran who erected the additional clubhouse for workingmen, which acted as a catalyst for local sports.

While the NYAC focused more on the elite, Cochran’s addition reached working class boys, and helped develop local competition. For an annual fee of eight dollars, a member enjoyed a variety of social and athletic activities. The Hollywood AC developed a fine reputation, especially from its baseball and basketball teams, while local industrialists helped popularize basketball by adding gymnasium space. As urban industrial communities grew, local YMCAs and Settlement Houses also added indoor athletic facilities. The Hollywood club set high standards for local athletes while receiving extensive news coverage in the local Yonkers Herald. Its reputation helped attract young Joe Lapchick.

* * *

Basketball appeared in Yonkers around the turn of the century. It wasn’t long before the tall youngster heard friends talking about it in Public School 20. The game seemed easy enough, and Joe Lapchick became interested. He waited impatiently for school to end and rushed to Doyle Park to play with real basketball rigs cemented into the ground and practiced until the older fellows chased him.

But there was another place for him to go play during the winter when it was cold.

Coach Oscar W. Kalkhof liked donating his time two nights a week to help Pastor Charles Cate of the Immanuel Chapel Presbyterian Church on Nepperhan Avenue. The pastor had the idea a few months earlier to open the church basement for neighborhood boys to play basketball.

“Three cents for the hour, please,” Coach Kalkhof asked a tall, thin boy the others called Joe. The tall Czech reached into his pocket and found he had enough for two hours. He dropped the pennies into a church collection basket by the entrance. The pastor made the youngsters pay to cover the expenses of heating and lighting the dim makeshift gymnasium with its two baskets.

Joe was ten years old but was attracted to a game that favored his height. After playing informal games for about a half hour, Coach Kalkhof lined up the eighteen boys and gave them a lesson in fundamentals. Since Kalkhof was a YMCA recreation director and a basketball official, he started with the rules and followed with some basics. He taught them that they couldn’t move both feet without bouncing the ball and not to punch an opponent. The coach showed them how to shoot and pass the ball with an even two-hand follow-through. He was a meticulous instructor, whom Joe credited as his first coach.

By the time Joe was twelve, he grew to 191 cm and weighed 64 kg, extraordinary height for the times. The youngster’s size, however, did not go unnoticed. As basketball blossomed in Yonkers, competitive youth programs were interested in the big Czech. The Holy Trinity Midgets from Joe’s parish church had a starter team coached by a burly Smith carpet weaver named Johnny Mears.

“Would you like to play?” Mears asked. “Sure,” he answered. The Midgets gave young Joe his first taste of organized ball. He later joked he was "the biggest midget around." He smiled recalling his "great floor game," spending much of his time stretching out on it. The youngster was ungainly, but his early clumsiness motivated him to improve and pay attention.

As Joe played games in 1912 with the Midgets and grew to enjoy the sport, he noticed other teams were dressed better. They had fancy jerseys with their team’s names emblazoned across the chest while his team played in their undershirts. “Why can’t we have shirts like that, too,” he said to his teammates. His prayers were answered when he received a large piece of felt from a hatter in the neighborhood.

“Mom, could you sew letters on my team’s shirts?” her son’s begging eyes asked after dinner one night. Frances Lapchick looked at the piece of gray felt, and then back into his pleading eyes and agreed to help. TRINITY MIDGETS was sewed diagonally on the front of the shirts, from the right armpit to the left hip. Joe liked it, and thanked his mother with a big hug and kiss. “To this day,” Lapchick insisted, “I can still vividly remember those shirts.”

* * *

By 1912, Mr. Lapchick was tired of being a hatter and motorman. He studied the civil service exam for policeman with his brother-in-law, Henry Kassik, and they took the test. Both thought they had done well on the competitive exam but weren’t giving up their jobs. Then one day in March of 1913, Mr. Lapchick received an official-looking letter that happily announced he “passed the exam” and would be contacted about joining the Yonkers’ police. As he danced with Frances around their kitchen table, her brother, who also passed, joined the celebration.

“Let’s go to Greasy George’s Restaurant for a Ruppert’s to celebrate,” Henry Kassik shouted as he hugged his brother-in-law. “It’s not everyday we join the Yonkers police force.” Joe agreed, as they headed to the Nepperhan Avenue restaurant.

Both remember March 13, 1913, as the day their lives took a positive turn. When Mr. Lapchick was later assigned to traffic in Manor House Square in the heart of town wearing his uniform and rounded “Keystone Kop” hat, he felt he was contributing to the community as well as his family. His better salary and benefits allowed the Lapchicks to rent a row house on Hog’s Hill that resolved their cramped housing.

Yonkers, like ancient Rome, was divided into seven hills, each with distinct ethnic roots. While the Hollow was the refuge of Slovakians and Park Hill housed Italians, Hog’s Hill originally attracted antebellum immigrants from Ireland’s Potato Famine. The Lapchicks’ row house at 26 Moquette Place was up the hill from the carpet factory, six blocks from their former tenement. "I remember," his son, Joe Donald Lapchick recalled, "walking down a steep hill on cinders to get to my grandparents row house." Lacking conveniences, it nevertheless served the Lapchicks well, providing the best living quarters the family had known.

"My grandparents had a nice row house,” said Jack Hopkins, the son of Anna, one of the four Lapchick daughters. “There was a hall and on the right a flight of stairs to four bedrooms,” Hopkins recalled; “two were small; a living room and kitchen, downstairs there was no dining room, everyone ate in the kitchen.” The bathroom was in the basement. It had a dirt floor. The boys put in concrete years later. Jack remembered a shed in the back for garbage, and he recalled as a child bathing in "the old stone tub in the kitchen,“ where his grandmother did the family laundry.

Hopkins, who had come from a broken home, admired the tight-knit Lapchick family that gathered regularly for holidays. Whether seated around the first floor kitchen table for Christmas or Thanksgiving dinner, card playing or helping to brew Mr. Lapchick's potent beer in the dirt-floor basement, the family came first. His grandparents taught moral and practical values while respecting the law.

Jack remembered the three Lapchick boys involved with sports. Young Joe and his friends played baseball up the street from their house in Smith’s Field, which they called “The Oval” because of the circular path near its open field.

After they moved out of the Hollow, Joe, who was approaching thirteen, continued playing basketball with the Midgets. The team had given him a clearer sense of basketball and made him realize how much he had to learn. Like most youngsters who grew rapidly, there was awkwardness to his game that made him stumble and spin out of control often landing on the floor as the others raced up court.

Unhappy with his clumsiness, Lapchick began a nightly, self-imposed training program on the cinder roads in the back of the carpet mill until he mastered his coordination. He ran at full speed, stopped suddenly, pivoted, changed direction, ran backwards, and shadowboxed. There were no coaches to correct errors or motivate him, only his determination and athletic instincts to guide him. He enjoyed working by himself, something he would do the rest of his life when he wanted to improve. With hard work he got better.

Like most working class people in Yonkers, Mr. Lapchick believed after grammar school his children should find steady work. When Joe completed eighth grade, he took a job with the Ward Leonard Electric Company in Bronxville at fifteen cents an hour on a 10-hour a day basis. But as he grew taller and improved his skills, he was ready to be paid to play.

As young Joe continued to play and grow, his talents became better known in Yonkers. The Hollywood AC, one of the better-known youth teams, often traveled to other towns to play. Joe dreamed of playing for them, a team with magic about it.

The Hollywood athletic club on South Broadway and Hudson Street had wonderful facilities. While Joe looked to expand his skills, he had no idea it would springboard him into professional basketball and change his life.

* * *

“The Czech kid is really good,” George Pettus, the Knights of Columbus basketball coach insisted. Lou Gordon, sporting goods proprietor and manager of the Hollywood AC, looked up. “How good?” he wanted to know.

“Well, he’s the tallest kid I’ve ever seen. The other night I saw him block a shot and tip it to a teammate before it went out of bounds.” Gordon hadn’t heard of too many shots being blocked in a Yonkers game. “Where does he play?” he wanted to know.

“I saw him in town against a good Bantams team with Billy Grieve, and he was the best.” The Bantams were an up-and-coming semi-pro team that was starting to catch on and were playing games upstate. “He can pass, make free throws, but most of all he can control center jumps,” the excited coach related. Gordon thought while he rubbed his chin. The rules called for a center jump after a score, and the big kid could control ten or twelve of them a game, which added to a team’s offense.

“What’s the kid’s name,” the sporting goods owner asked? “You know him, Lou. He’s the big foreign-looking kid who hangs around the store three, four times a week; his name is Joe Lopchick or Lapchick. It’s always misspelled in the papers. He’s from over by the carpet mill, and he’s got to be every bit of 196 or 198 cm.” Gordon made a mental note to pay attention to his tall customers in the future.

A few days later on a sunny Saturday afternoon in October, a tall, thin blond teenager made his way over to the heart of Yonkers’ shopping area and Lou Gordon’s Sport Shop. Young Joe Lapchick was familiar with the store. After work and when not playing, he often walked to the Palisade Avenue store to listen to Yonkers sports talk. When he entered he spotted the latest Louisville Slugger ash wood baseball bats and smelled strong cowhide from a shipment of Reach gloves in the rear of the store.

Joe particularly liked the galvanized rubber aroma of the latest basketball sneakers, which he could only dream about. They were fancy with black stripes over the white canvas tops. He liked the suction cups, which helped prevent slipping on the dusty courts he played on. The Spaldings black ankle patches identified the manufacturer, but to the young athlete they made the sneakers more attractive and added class. He loved the white laces and wished he had the $1.95 to buy a pair.

Joe knew sneakers didn’t last long playing with the Trinity Midgets. The pair he wore had a large piece of folded newspaper that covered the half-inch hole boring through the rubber sole of his right sneaker. As he inspected the new sneakers, he wondered how long he had to work in the factory before he could buy them. But as the oldest of seven children, his factory wages were needed to help his family. For now the sneakers remained a dream.

“Like those sneakers?” Lou Gordon asked. “You’re the Lapchick boy,” Gordon concluded before the shy giant could answer. Towering over his inquisitor, Joe could only nod his head and look away. But Gordon wanted to talk to the youngster and decided to discuss what had to be his favorite subject.

“I hear you like basketball?” Joe looked up from the sneakers, saw a dark-haired man with a medium build, and again nodded. The storeowner noticed the threadbare condition of his sneakers. “Would you like a pair of those sneakers?” Gordon offered with a smile. There was no hesitation now. “Yes sir,” he answered. “Well, Spalding gave us a few sample pair of that new model, and if I have your size in stock, you can test-wear them for us.”

Joe couldn’t take his eyes off the brown box under the arm of the owner as he returned from the stock room. Wow, he thought, a new pair of Spaldings. “Thank you, Mr. Gordon,” the boy’s good manners kicked in as he reached for the large box. But as he turned to leave the store, Gordon asked one last question.

“Joe, would you like to play for the Hollywood AC?” Two Christmases in one day was more than he could handle. Joe turned, faced the smiling owner, and more than nodded. “Yes sir, I sure would.” Gordon explained that he was the manager of the team and told the tall youngster to report next Saturday morning to Coach Jim Lee for a tryout. “Coach Lee will take care of you.”

Joe was shocked. The Hollywood team picked school stars, and he felt he didn’t have much of a chance. Besides their overall talent, he would battle local star center, Jimmy Herald, whose experience exceeded his. “Do you think I have a chance?” the soft-spoken youngster asked. “Sure, sure you do, Joe; just show up at the gym, and I’ll tell Mr. Lee you’re coming.”

As Joe walked home with the brown box firmly tucked under his arm, he thought of the club’s tall building on South Broadway and Hudson Street with its lofty reputation. He wanted to make the team and a name for himself. As the oldest Lapchick, he wanted his folks to be proud. He could do it.

Sporting his new Spaldings, Joe arrived at the Hollywood gym thirty minutes before the nine a. m. tryouts. The magnificent gym was on the first floor along with its locker room and more than four hundred lockers for its members. He had never seen an athletic facility with as much for its patrons. Bowling alleys, billiards, showers and a pool were some of its offerings.

As he entered the gym a gentle-looking man with a shock of red hair and a confident way greeted him. “Hi, I’m Coach Jimmy Lee, and you must be Joe Lapchick,” he said as he extended his hand. “Take a locker and warm up.” Unknown to the young center, an introductory note was sent to the coach. “Here’s the Hollys’ new center,” Gordon predicted.

When the team assembled, Lee ordered two lines for lay ups and barked corrections as he and two other men scrutinized the players. Joe felt self-conscious after a missed lay up and absorbed the sting of constructive criticism, but after watching him play Lee found the young Czech learned quickly and worked to improve.

After two weeks of intense practice, Joe found his name on the list pinned to the gym bulletin board. Much to his surprise he made the team, beating out the local star. He was thrilled to receive a uniform. With his new purple jersey with “Holly” diagonally across the chest, a script bar under it, number twenty-two on the back, and purple knee-high socks with white stripes, he was ready and anxious to play.

Making the Hollys was the first major accomplishment in Joe Lapchick’s basketball career. Lou Gordon’s sneakers and the Holly team were warm memories for him. Gordon’s suggestions changed his life. The confidence Lapchick gained led him to the Bantams, another powerful Yonkers team, which opened doors to budding pro promoters. However, he never forgot the sporting goods owner’s kindness and guidance.

Lapchick started attracting attention as a fifteen-year-old. While playing for the Hollys, Joe also joined the powerful Bantams. They set dates, fees, and were usually paid by “passing the hat after games.” On other occasions home teams charged a modest fee to cover expenses, but in either case the young Czech was getting an education as he began to play for pay.

Playing simultaneously with the Bantams and the Hollys caused the Yonkers Herald to wonder which team he’d choose when they played each other. This was a nice problem young Joe faced as his skills and reputation increased. After an outstanding game where he had scored five field goals and four free throws of the Hollys twenty-five points, the local newspapers snapped his photo. Standing straight, arms folded behind his back, wearing heavy-duty knee guards, Joe Lapchick, with a serious but proud look, was ready to make a name for himself in basketball.

“Big Joe” was directly asked whom he would play with when both teams clashed later in the season. It was a tough decision. But, the sportswriter suggested, he had to choose because he was “too good to sit out a game and deprive fans of his skills.” But no matter what he decided, the sportswriter thanked the young Czech for “putting Yonkers on the basketball map.”

While playing night and weekend games in 1916 with the Bantams, Joe experienced his first taste of professional play when he earned three dollars for a game. Although he enjoyed local popularity, he was thrilled someone would pay to see him play. Representing Ossining, and playing their home games in Yonkers’ Columbus Hall, the Bantams traveled to nearby Beacon, Wappinger Falls and Hudson, and he netted $15, then $18 in successive years.

Joe Lapchick’s value was becoming known and his services sought. What followed was a whirlwind of neighborhood teams vying for “the tall Yonkers kid” who moved freely into "play for pay" basketball circles. While he was gaining experience and a reputation, he maintained his job as a machinist in a local factory and caddied in the off-season. When he had time, he pitched sidearm for the Federal Sugar Refinery. His life was filled with sports.

Lapchick's excitement for basketball, however, did not initially meet with parental approval, and he was forced to hide his uniform. His father's stern foreign upbringing made it difficult for him to understand why his son ran around in short pants and an undershirt. "Joe, is that what you wear when you play?" The affirmative reply further confused his father, who considered the outfit unmanly.

The expanding economy along with the nation's rising sports interest helped Lapchick’s career to blossom. When his income surpassed his father's, he no longer hid his uniform. Mr. Lapchick saw matters differently. Joe’s brother, Bill, verified this feeling. "Up to then my father had been puzzled and a little disturbed. But when he saw the money roll in, he changed his mind.”

* * *

Pre-war professional basketball was part of a free market system that created a bidding war for top talent, which catapulted young Joe Lapchick into the enviable position of having teams chasing him lining up to pay him to play. Unlike baseball with its reserve clause that denied players a choice of teams, basketball’s competitive market caused game fees to skyrocket for quality players. He was tall, fast, and talented. "I was getting a local reputation," he remembered, which led to games during 1916 -1917 season with the best teams in New York City.

Demand increased Lapchick’s bargaining power and made him a valuable property, to the point where he played on four teams simultaneously. With center jumps after every score, he controlled the taps and rebounds vital to a team's success. He began to realize that his size, once an embarrassment, was now helping him to high earnings in the new game.

The more he played the greater the demand for his talents. On each rung of the ladder he learned to ask for more money, and usually got it. The truth was he could play with as many teams, as often as he wished.

While playing for the Hollywood team in Manhattan against the well-known and talented Whirlwinds, Lapchick caught the opposing manager's eye. For seven dollars a game, a factory worker's weekly pay, Lapchick made frequent trips into New York. At eighteen, Lapchick’s amazing popularity encouraged his basketball stock to rise. Most pros like Lapchick switched teams if offered five dollars more from another manager. There was no team loyalty, with money the only bargaining chip that influenced their decision.

Lapchick's salary continued to rise, and as a member of so many teams, he could play most nights. With teams playing twice a week, it was impossible to satisfy each manager, and he jumped from one team to another. By playing one team against another, he increased his earnings dramatically. The going rate started at a dollar a minute, but it didn't take him long to figure out his true value. At this point Joe Lapchick was a professional player, one who was completely consumed with how well he could play. Their individual performance, points scored and defense evaluated star players.

Gradually he got to know the game's best players at Grand Central Station in Manhattan, who often met there determined to create a bidding war for their services. Well-known performers like Honey Russell, Benny Borgmann, and Elmer Ripley began showing Tall Joe the ropes. Grand Central became the marketplace where they telephoned regional teams about their fees. From there they boarded trains to the best payday. As word of Lapchick's value made the rounds, he parlayed his skills into more money than he had ever seen. He quickly learned how to promote himself.

* * *

“Any talented players in Yonkers?” Holyoke Reds coach Tom McGarry asked his star guard, Dave Wassmer. Like every other team in the Western Massachusetts League, the Reds were searching for a big man. “Everybody is talking about this big Czech kid.” Wassmer then described the tall lanky 196 cm center who was making a name around Westchester. “I think he can help.”

Semi-pro basketball involved a roller coaster of teams in Eastern leagues springing up overnight, struggling, and disappearing as quickly. But in spite of the game’s instability, Lapchick’s size was always in demand.

He was nineteen and almost 2 meters tall when he joined Holyoke. Newspaper accounts heralded his effectiveness when he set a league record the first game. He was quickly established by canning all eleven of his free throws. The record "gave me a reputation," Lapchick recalled. "Now I was a full-fledged pro." But the industrial town was not prepared for the excitement stirred by Lapchick's size.

Unusually tall, Lapchick was treated as if part of a traveling circus. The Holyoke townspeople gawked as he walked the streets after a game, calling him a gypsy, freakish. People over 2 meters tall were rare, while players over 210 cm in height didn't exist. However, growing up, he learned to handle the taunts of hecklers.

By 1919, Lapchick, who earned fifteen dollars a week as an apprentice machinist, was making ten dollars a game, four to five nights a week. He and his family began to live better. By the early 1920s, besides Holyoke, and occasional games with Hollywood, Lapchick played for Schenectady and Troy in the New York State League, and for the well-known Whirlwinds. The exposure with them led him to the Brooklyn Visitations in the Metropolitan League. Since their games were on Sunday nights when other teams were idle, Lapchick played with them. While he learned to bargain with managers, his rates gradually increased until they reached ninety to one hundred dollars a game no matter how many minutes he played.

Teams fought for the right to pay him more money than he or any member of his family had ever earned. What he demanded he got. "I was making so much money I became a big shot," he recalled with a smile. He bought a gray deluxe DeSoto roadster with a rumble seat and parked in front of the Knights of Columbus Hall, threw his bag in the air, and escorted a Yonkers youngster who caught it into the game free. He learned this trick from local star athletes Larry McCrudden and Ray Wertis, who extended the same courtesy. He was now the star.

When the season ended, Lapchick returned to golf and baseball, which were still off-season passions. Shortly after his nineteenth birthday he received a serious baseball offer. “I liked to pitch,” Lapchick recalled. As a tall, strong sidearm pitcher he had something to offer. The Brooklyn Dodgers and their manager, “Uncle Wilbert” Robinson, were interested and sent a scout to check him out. When the reports were favorable Robinson offered him a Dodger contract.

Lapchick considered the offer a high point as well as a crossroads. After some thought he turned down the Dodger offer and stayed with basketball even though it was in its infancy. “I had been doing well playing in New England and upstate New York.” During this transitional period he would advance from a series of semi-pro Yonkers teams to a championship with the Holyoke Reds.

* * *

"Inter-State League 1921-1922 Champions," the caption on the photo read. Six durable-looking players and a manager immortalized the Holyoke Reds championship. A bloated-looking leather basketball, huge by today's standards and more like a summer beach ball, rested between the feet of two players. Few of today's NBA pros could palm this "pumpkin." Each player wore large, heavily padded knee guards (as if they were ready for combat in some futuristic war) and sported worn leather high-top shoes similar to a boxer's footwear. Each player was neatly dressed in a dark-colored, woolen v-neck sweater with a large red "H" sown on the chest, and not a hair out of place. Like most team photos, shorter players benched up front. The guards seemed uncomfortable with their hands, not knowing where to stick them. The tallest two players standing in the rear sandwiched the manager, Tom McGarry, who was nattily dressed and seemed proud of his team’s success. To the left, a huge, small-mouth, lantern-jawed 193 cm bruiser dripped confidence. Hair parted down the middle, eyes straight ahead with a look that dared the photographer to make an error. On McGarry's right stood the tallest but youngest-looking. Joe Lapchick must have been distracted as the camera clicked. With his body tilted left he looked right with a genuine smile that radiated satisfaction. This was his first professional championship, and the Big Czech was enjoying it.

* * *

One of Joe Lapchick’s unforgettable early professional experiences was playing for McGarry’s Reds. There wasn't much to encourage team managers since early pro basketball didn’t attract baseball crowds. Besides being unprofitable the pro game in the early 1920s was slow moving, brutal, and primarily played by working class athletes. While the game struggled with its social image, promoters paved its future.

A newspaper printer by trade, McGarry was typical of the times. Like most managers he operated the team “out of his coat pocket.” The Reds’ small crowds forced the team to exist under minimal semi-professional standards. They enjoyed no sponsors and survived by promotions and passing the hat. The Reds were one of the first teams to sponsor dances between and after games to draw crowds.

While the team struggled financially, McGarry’s reward was wrapped in pride. Turn-of-the-century political bosses suffered a similar exhilaration. They, too, enjoyed standing on street corners puffing their chests when "their man won." The same boasting propelled early sports management. McGarry, like the young Czech, was a pioneer of basketball and loved every minute.

The game's rowdiness made caged playing areas popular and necessary. While the rope or wire cages kept the ball in play, it also restrained hostile fans from inflicting punishing pranks on visiting players. The 366 cm high cages, however, lost their popularity by the early 1920s, but not before permanently labeling players cagers.

Despite McGarry’s charming Irish wit, which he used on opposing managers, many games ended with heated confrontations requiring a quick backdoor escape. It was not unusual when the Reds won on the road to need a police escort out of town. During a game against Chicopee, an intoxicated fan was heaping verbal abuse on Lapchick to the point that he threw the ball into his face. He was thrown out of the game in the second half, but not before he scored nine vital points in the victory.

After the Reds had faded into the past, McGarry still enjoyed boasting about Lapchick's success. The old coach’s quick tongue was in the habit of ricocheting one-liners or player nicknames. Lapchick was "Bohunk," a name tied to his obvious Bohemian background, but when he coached the Knicks, McGarry labeled him, like many others, "Lunkhead." Once, in the late 1940s, McGarry took his son to see the Knicks in the Garden. As they approached Lapchick from the rear the former coach slapped him so violently that the blow almost knocked Lapchick down. Life was never dull around McGarry.

* * *

By 1922, after Lapchick had been pounded in games by the aging Horse Haggerty of the Original Celtics, rumors circulated that their owner, Jim Furey, was interested in the tall Czech. Haggerty, one of the game’s most physical players, was thinking of retiring to a small farm in Reading, Pennsylvania. With Haggerty hanging up his sneakers, it was Lapchick’s time. But just to make sure, Joe wanted to discuss his future with Dave Wassmer, a Yonkers friend and Holyoke teammate.

“I think I’m going to sign with the Celtics,” he admitted to Wassmer, as he lit a new Turkish blend Fatima cigarette. Older by five years, Dave knew how difficult making a living from pro basketball was in the early 1920s. “Why, Joe?” he wanted to know. “There’s no security in basketball.” Dave had gone to a few years of high school and was heading into business after his playing days. “Banking’s steady; everybody uses banks,” the stocky guard reasoned.

Joe thought about his friend’s advice, but basketball was in his blood, and he wanted the chance to play the best in the country. “I only went to grammar school,” Lapchick said. “Basketball’s what I’m built for. I’m 196 cm and I love this game, and, besides Mr. Furey promised me a guaranteed contract.”

“Maybe you’re right, Joe.” Dave thought it might work out. It’s what he knows, and maybe all he knows, and surely what he wants. “But I still think you’re crazy taking the chance,” Dave warned. Joe smiled and grabbed his friend around the neck and wrestled with him in a fun way to let him know how much he appreciated his concern. But it was the Celtics he dreamed about, and the Celtics he would sign with if they would have him.

By the 1920s, Jazz Age Americans had transformed into a leisure-minded nation, receptive to most amusements. Americans wanted to be entertained. Willing to climb flagpoles and swallow gold fish, the nation was also fascinated with sound films, Broadway shows, and sports. Sports were part of the country's entertainment. While baseball, boxing and horse racing interested fans, professional basketball was trying to form a national league.

Lapchick had traveled with the Hollys and Bantams earning five dollars a night while struggling to master a rugged and demanding game. He made stops along the way with the Holyoke Reds in Massachusetts, New York Whirlwinds, Brooklyn Visitations, and eventually was chased and signed by the Celtics. Along the way, he learned how to play and bargain his talents.

At this critical but golden moment in sports, a gangly string bean of a young giant joined the Original Celtics. He learned to play better as well as dress, socialize, and conduct himself in an acceptable fashion. For him, basketball was the thread that bound his life together, and the shining light that directed it. It was the opportunity of a lifetime for Joe Lapchick. And as he traveled he learned to act like a pro, a classification that meant the world to him.